When I was in college, my favorite singer-songwriter was a guy named Rich Mullins. If you aren’t a member of Gen X or a millennial, or if you didn’t grow up in the evangelical church, that name probably won’t ring any bells. A gifted multi-instrumentalist, Mullins composed staples of contemporary worship music like “Awesome God,” “Sometimes by Step,” “Creed,” “Hold Me Jesus” and “Sing Your Praise to the Lord.” Many Christian artists trace their careers back to his influence. Mullins could have achieved fame with his songs alone, but many also remember him as an unwashed, cigarette-smoking firebrand who lived on a Navajo reservation and consistently challenged his era’s religious status quo. During a concert that took place shortly before his untimely death in 1997, Mullins said the following:

Jesus said, ‘Whatever you do to the least of these my brothers, you’ve done it to me.’ And this is what I’ve come to think: that if I want to identify fully with Jesus Christ, who I claim to be my savior and Lord, the best way that I can do that is to identify with the poor. This, I know, will go against the teachings of all the popular evangelical preachers. But they’re just wrong. They’re not bad. They’re just wrong. Christianity is not about building an absolutely secure little niche in the world where you can live with your perfect little wife and your perfect little children in a beautiful little house where you have no gays or minority groups anywhere near you. Christianity is about learning to love like Jesus loved, and Jesus loved the poor and Jesus loved the broken-hearted.

This concern for marginalized people is, more than anything, what drew me to Mullins. In his songs and stories, I heard the beating heart of Christ – Jesus’ command to “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44), which he exemplified by pardoning his killers on the cross (Luke 23:34); his requirement that his disciples sell their possessions and give the proceeds to the poor (Luke 12:33); his friendship with “tax collectors and sinners” (Matthew 11:19), which scandalized Israel’s complacent majority; and his table-flipping protest against economic injustice at the Jerusalem temple (Mark 11:15-18). This same heartbeat is loud (and proud) in the music of Derek Webb – a singer-songwriter who once drew inspiration from Mullins and Christ and who now writes songs about LGBTQ+ experiences outside the walls of the Christian church.

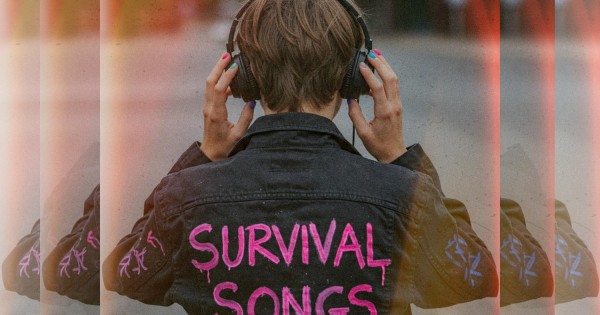

Formerly a member of the award-winning band Caedmon’s Call, Webb was known for pushing the envelope of Christian music well before his deconversion. He embarked on a solo career in the early 2000s, releasing a string of critically acclaimed albums – She Must and Shall Go Free (2003), Stockholm Syndrome (2009), and I Was Wrong, I’m Sorry, and I Love You (2013) among them – that championed social justice causes and challenged mainstream evangelical attitudes toward religious and cultural outsiders. In 2017, Webb released Fingers Crossed, an album that explored his personal experience of spiritual deconstruction. Six years later, he followed that up with The Jesus Hypothesis, in which he reflected on the legacy of his former faith. Now, Webb has just released his thirteenth solo album, which he describes as “nine songs of empowering, encouraging soundtrack for my loved ones and my friends in the queer community.” Self-produced and written within the span of one month, Survival Songs isn’t just Webb’s best work to date; it’s a bold call for empathy in a chaotic, frightening, and deeply polarized time.

The album’s first track, “Queer Kid,” opens with a stanza that immediately sets the stakes for all that is to come:

Growing up, she heard about the end times

But they never felt so close

If showing love could make you a criminal

And wearing your own clothes

These lines reference the flurry of anti-LGBTQ+ executive orders that followed Donald Trump’s inauguration in January of 2025, which rolled back (“like a tape stuck in reverse,” as Webb sings) decades of legislation designed to protect queer people from discrimination (even though Trump himself once supported such legislation) and also sought to erase trans people as a cultural category. Buoyed by rhythmic guitar strums and syncopated piano chords, Webb takes aim at the evangelical church’s justification of hateful rhetoric in the bridge of the song:

Why don’t they call it what it is?

Wholesale gendercide aimed right at the kids

While their own holy book says ‘Love your enemies’

And ‘All the little children, let them come unto me

Meanwhile, they’re so busy changing all the rules

Building up the kingdom using all the devil’s tools

They forgot the way history’ll show just what they did

By then there’ll be green grass growing on the grave

Of that queer kid

In “Nail Polish,” Webb describes his custom of wearing nail polish in public. Such an act might seem innocuous, but it draws lots of questions, and it’s also not primarily for Webb’s enjoyment. The singer explains in a video posted on his YouTube channel:

While it is a fun and easy way to challenge gender binaries, it turns out painted nails are a fantastic early warning system when I’m out in public with my queer family and friends. Potentially unsafe, homophobic and transphobic people cannot help but stare and out themselves. So when me and my painted nails walk into a room, I get a quick sense of who I need to watch out for to help keep my people safe.

Webb’s strategy might seem like overkill if you aren’t unacquainted with statistics on violence toward LGBTQ+ people in the United States. According to the Human Rights Campaign, “More than 1 in 5 of any type of hate crime is now motivated by anti-LGBTQ+ bias” (emphasis mine). FBI data shows that attacks based on gender and sexual orientation are rising quickly, to the extent that LGBTQ+ people are now five times as likely to be the victims of violent crime as their straight and cisgender counterparts. When Webb sings that “you gotta plan ahead and be brave / and pick a shade,” he’s dead serious. His queer loved ones are at risk in ways he’ll never be.

Webb makes this distinction clear in “Stay Safe,” which begins with a haunting choral intro: “It does not require bravery to face the world as I am… But I see you weighing life and death / every day in your skin.” I’ll never forget listening to my first trans friend describe their terror after hearing of a gender-based murder near their hometown. Such realities temper and complicate Webb’s desire for his queer loved ones to engage acts of public protest: “You gotta stay safe out in the open / I want you free, but I need you alive.”

The fourth track on Survival Songs is sonically warm and upbeat, but it tells a painful story of self-harm that is familiar to many in the LGBTQ+ community. The Trevor Project’s 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of Young People found that 54% of queer youth reported self-injuring that year; of those youth, 59% also considered suicide and 27% attempted it. Reasons for self-harm are often complex, involving factors such as shame, trauma, loneliness, confusion, and social rejection. However, the journey of healing and self-acceptance may be catalyzed by simple acts of love, like the handwritten note that a barista tucked into the coffee cup of Webb’s wounded friend: “I was there too. It won’t be this way forever.”

Track five, “Muscle Memory,” is a love song that depicts the difficulty of lowering our inner defenses and building trust with someone different than us. Webb’s wife, Abbie Parker (formerly of the Christian band I Am They) contributes to the duet. On “Sola Translove (Words of Meditation),” above a shimmering bed of plucked strings and gentle piano notes, Webb repurposes a benediction that is used in many churches, evoking both the transcendence of love across boundaries and the queer “cloud of witnesses” that surrounds those he loves:

Above you, below you

Before you, behind you

With you and for you

Sola translove

“In your place” is the standout song on an album of great songs. Over hauntingly beautiful fingerstyle guitar riffs, Webb plays with different meanings of the phrase “in your place,” pondering the temptation to conform to societal expectations in the midst of an unsafe world, the challenge of viewing life through another’s eyes, and the encouragement of those who have faced similar injustices. The song’s final stanza references the “chosen family” that queer people must regularly seek out, as their biological families (and church families) often refuse to accept them as they are and, in many cases, ostracize them. Community with like-minded others, whether in the present or throughout history, offers potentially life-saving courage: “You could be like them / ’cause they’ve all been / in your place.”

Survival Songs climaxes with the hymnic track “This May Be the Time to Close Your Eyes” – a track that contains some of Webb’s most stunning lyricism to date. The song opens simply and builds to a thunderous crescendo as, in a style reminiscent of the folk troubadours of the civil rights era, Webb surveys the landscape of American society – its fake news and censorship, its authoritarian government and denial of basic human rights, its collusion of church and state and oppression of vulnerable populations. What begins as a call to brace for the worst eventually transforms itself, as soft and luminous as the dawn, into a vision of what the world could someday be:

But listen softly for the sound, the burning fuse

Igniting painters, activists, prophets bringing news

Of families, stories, hearts and minds opening wide

The hopes of all the painted bruises realized

Of all god’s children’s thriving lives, may this be the day

Of husbands and husbands, wives and wives, may this be the day

When beauty’s beauty and love is love, may this be the day

Thank god you’re safe and you’re enough, may this be the day

When all the faceless hear their names, let this be the night

When all the shapeless rest in frames, let this be the night

When all the tears are wiped away, let this be the night

When all true justice falls like rain, let this be the night

Child, this may be the time

Open up your eyes

In the album’s closing track, “Sola Translove (Words of Affirmation),” Webb wisely steps back, allowing his queer friends to share their perspectives. Words of encouragement swirl into a simple refrain that is repeated over and over: “You are loved. You are loved. You are loved.”

I spent decades of my life memorizing scripture, and I can assure you that these final songs sound much closer to the Bible’s vision of justice (and much closer to Jesus’ own words about marginalized groups) than Donald Trump’s pseudo-religious fearmongering ever has. This should come as no surprise. Derek Webb actually believed in the Christ that Trump pretends to worship. Additionally, unlike Trump, he’s still committed to advancing Christ’s vision of unconditional, self-giving love across ideological borders. Webb may not agree with all the beliefs that his former hero, Rich Mullins, espoused, or with everything that Jesus said and did. But I have a feeling that both men would be proud of him. I certainly am. By standing in solidarity with his queer brothers and sisters, he’s showing us – just as the Biblical prophets once did – the world we dream about, which has never been out of reach.

May this be the day, indeed.

This made me cry 💙

LikeLike