In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov, there’s a scene where two brothers, Ivan and Alyosha, are discussing religion in a tavern. Ivan is a skeptic, and he objects to God’s goodness on account of the world’s suffering. According to Ivan, the future “harmony” that believers long for, where all sorrows will be consoled and all wrongs made right, can’t justify the suffering that God allows in the present, especially the misery of children. If God’s future world depends on such suffering, then Ivan doesn’t want any part of it:

I don’t want harmony. From love of humanity I don’t want it… I would rather remain with my unavenged suffering and unsatisfied indignation, even if I were wrong. Besides, too high a price is asked for harmony; it’s beyond our means to pay so much to enter on it. And so I hasten to give back my entrance ticket, and if I am an honest man I am bound to give it back as soon as possible. And that I am doing. It’s not God that I don’t accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return him the ticket.1

Whether or not we believe in a higher power, Ivan’s objections are painfully familiar to those of us who have reckoned with the world’s brokenness or have been broken by life ourselves. Standing in the rubble of our former innocence, we feel cheated and confused. We begin asking questions that, to borrow writer Maria Popova’s phrase, “raze to the bone of life”2: Why is the world we call home, the planet we long to love unreservedly, such a hostile place? Does life’s goodness depend on the decay and devastation that surround us? And if it does, do we want any part of the arrangement? Faced with these dilemmas, we muddle through life as best we can. Yet many of us, including Ivan Karamazov and a certain indie rock band from New York City, find ourselves stuck. We aren’t kids anymore, and we can’t settle for easy answers. We have entered the dark night of the soul.

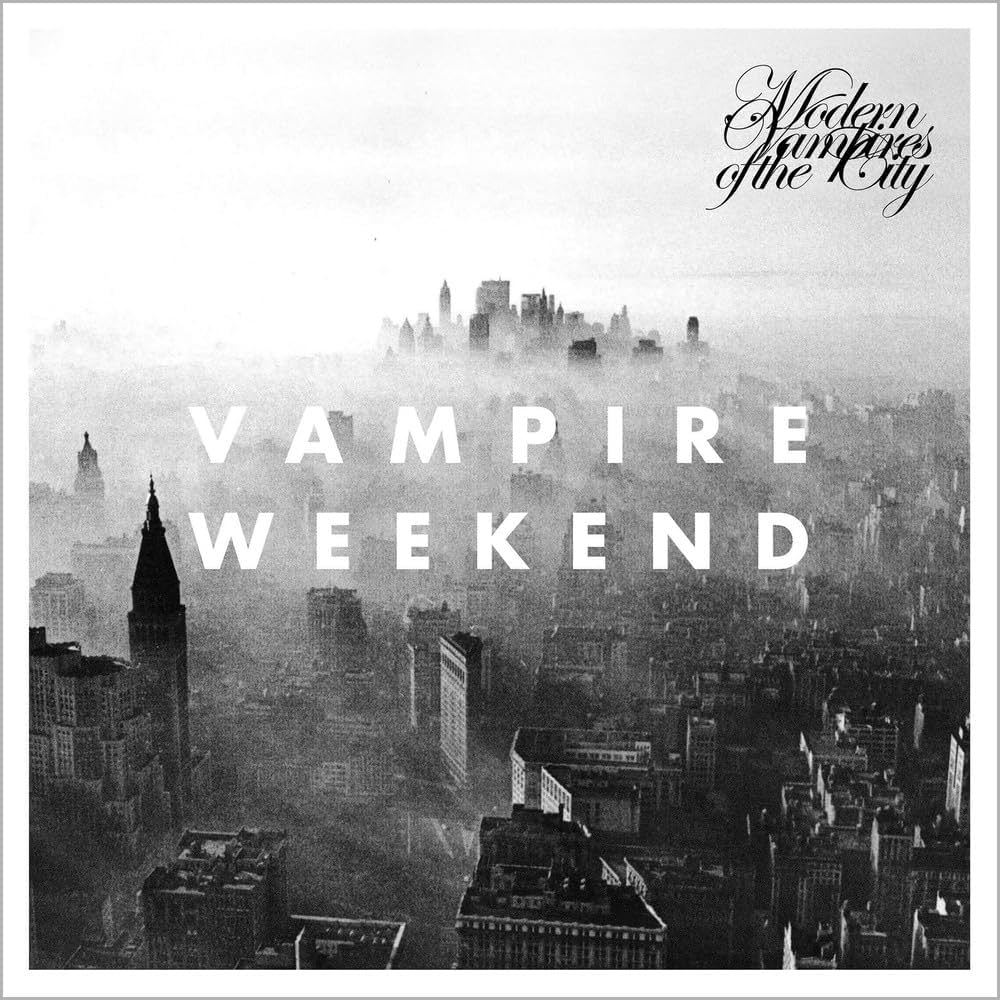

If Vampire Weekend fans expected anything after the band’s debut and sophomore albums, 2013’s Modern Vampires of the City wasn’t it. A seismic shift had occurred, and its aftershock was impossible to miss. In stark contrast to the bright, whimsical covers of Vampire Weekend and Contra, the new album’s artwork featured a spooky, black-and-white photo of a New York City skyline shrouded in smog. The band chose the image for its dystopian vibe, suggesting (ominously) that it depicted “some kind of future.”3 In a brilliant artistic stroke, their hometown was rendered unfamiliar, foreshadowing the displacement and disillusionment that would drift like ghosts throughout the album’s songs.

The band’s music had shifted too, distanced now from the African and Caribbean grooves that infused their former records. The new tracks crackled with electronics, distortion, and layered production, lending the album a darker and grittier feel. Modern Vampires marked the beginning of Vampire Weekend’s long-running collaboration with innovative producer Ariel Rechtshaid, who joined Rostam Batmanglij behind the soundboard. According to Rechtshaid, the band had thrown away their sonic playbook, eager to explore uncharted territory: “Whenever we came up with something familiar sounding, it was rejected.”4 The effect was a disorienting one for many listeners, and that was exactly what the group wanted.

If Vampire Weekend’s new sound invited listeners to join them in the wilderness, so did lead singer Ezra Koenig’s lyrics. While still present on a couple tracks (“Step” and “Finger Back”), the cheeky wordplay of Vampire Weekend and Contra was largely gone, replaced with more straightforward meditations on life’s rough edges. If Contra dipped its toes into existential angst, Modern Vampires was a cannonball into the deep end, tackling a host of weighty topics: loneliness, aging, fear of death, alienation from modern society, grief, and loss of faith. As Koenig sings on the chorus of Modern Vampires‘ third track, “The gloves are off, the wisdom teeth are out.” The scrappy, wide-eyed dreamers from Columbia University had finally come of age, and they weren’t pulling any punches.

While not all of Vampire Weekend’s fans were thrilled by the new direction, Modern Vampires of the City was widely hailed as both a masterpiece and the band’s best work to date. Critics praised the scope and maturity of the project, and several publications declared it the best album of the year.5 In January of 2014, Vampire Weekend took home their first Grammy award for Best Alternative Music Album.6 For all its shadows, Modern Vampires had struck a chord with listeners. It remains my favorite Vampire Weekend record and, according to Rolling Stone Magazine, one of the greatest albums ever made.7

Throughout this series, we’ve analyzed the lyrics of Vampire Weekend’s albums, exploring the central question of their discography: How can we continue to love a world that has broken our hearts time and time again? On Vampire Weekend, we witnessed a narrator falling in love with the world. On Contra, we saw that same narrator developing a broader consciousness of the world and making uneasy space for its suffering. Now, on Modern Vampires, we’ll see our protagonist returning his ticket, offering a breakup letter to the world that broke his heart. It’s heavy stuff, but the music is thrilling and propulsive from start to finish.

Are you ready? Then brace yourself. It’s going to be a bumpy ride.

Analysis

Like the opening lines of Vampire Weekend‘s “Mansard Roof” and Contra‘s “Horchata,” the first two stanzas of “Obvious Bicycle” (perhaps my favorite Vampire Weekend song) depict the narrator taking in his surroundings. However, unlike the imagery of those earlier songs, this landscape is utterly devoid of warmth or comfort:

Morning’s come, you watch the red sun rise

The LED still flickers in your eyes

Oh, you ought to spare your face the razor

Because no one’s gonna spare the time for you

No one’s gonna watch you as you go

From a house you didn’t build and can’t control

Oh you, ought to spare your face the razor

Because no one’s gonna spare the time for you

You ought to spare the world your labor

It’s been twenty years and no one told the truth

Floating atop eerie percussion (which sounds, interestingly, like rattling chains or a pair of scissors opening and shutting), Koenig’s lyrics depict a planet insensitive to our welfare. The narrator likens this world to a house we “didn’t build and can’t control,” reminding us of a series of uncomfortable truths: We didn’t choose to be born, we don’t know when we’ll die, and we have a puny grasp of reality. Albert Einstein agreed: “Our situation on this earth seems strange. Every one of us appears here involuntarily and uninvited for a short stay, without knowing the whys and the wherefore.” Later in the song, Koenig wonders why people would fuss over their physical appearance, since we’re all destined to be forgotten by the societies we inhabit. His words echo those of the Biblical poet: “No one remembers the former generations, and even those yet to come will not be remembered by those who follow them” (Ecclesiastes 1:11). In light of these realities, detachment seems the safest course. Don’t put down roots that’ll only get ripped up, the narrator suggests. Better to “Take your wager back and leave before you lose.”

Listening to Koenig, we realize that the youthful optimism endangered on Contra is now irretrievably lost. The maps handed to the narrator by former generations have led him on a wild goose chase, triggering resentment: “It’s been twenty years and no one told the truth.” As the album unfolds, this cynical sentiment continues. The song “Unbelievers” opens with a mournful declaration: “Got a little soul / The world is a cold, cold place to be” Once, the vastness of the world was a summons to discovery. Now, it threatens to overpower the narrator, and there’s no guarantee that other people will come to his aid. Later, the song “Finger Back” lets loose a barrage of grisly images, examining the perennial strikes and counter-strikes that threaten to pull the fabric of society apart. With a tongue-in-cheek reference to the abandoned baroque instruments of their former albums, the band paints this picture with vivid, apocalyptic zeal:

The harpsichord is broken and the television’s fried

The city’s getting hotter like a country in decline

Everyone’s a coward when you look them in the eyes

But baby, you’re not anybody’s fool

The bridge of the song devolves into chaos, with the narrator screaming the word “blood” over and over. History is littered with corpses. Nature may be beautiful, but it’s also a bloodbath, filled with incomprehensible amounts of animal suffering. The narrator wants no part of this cycle of destruction, and yet he’s trapped inside of it: “I don’t wanna live like this, but I don’t wanna die.”

This fearful admission could be the thesis statement of the album, which explores the narrator’s anxiety regarding death with remarkable vulnerability. On “Step,” we discover that growing up has lost its appeal: “Wisdom’s a gift, but you’d trade it for youth / Age is an honor, it’s still not the truth.” The lyrics of the next song, “Diane Young,” reach the same conclusion: “Nobody knows what the future holds / It’s bad enough just getting old.” Like a good Irish comedian, the narrator confronts death with a sardonic smile, wielding humor to cope with heartbreak. The song’s title puns on the phrase “dying young,” and its lyrics reference both the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the poet Dylan Thomas (“Do not go gentle into that good night”), portraying life as a doomed car ride:

Irish and proud baby, naturally

But you got the luck of a Kennedy

So grab the wheel, keep holding it tight

‘Till you’re tottering off into that good night

Yet the narrator isn’t laughing when the song “Don’t Lie” rolls around. Here, his defenses drop, and we see him desperately trying to make sense of the fact that he and everyone he loves will one day cease to exist:

I want to know, does it bother you?

The low click of the ticking clock

There’s a headstone right in front of you

And everyone I know

Throughout Contra, we witnessed the narrator’s budding realization that failed romances leave lasting scars. The breakups on Modern Vampires of the City prompt full-blown existential despair. On “Step,” the narrator mourns his lover’s vulnerability and the prospect of irreversible loss: “Maybe she’s gone and I can’t resurrect her.” On “Hannah Hunt,” after enduring yet another heartbreak, he howls into the void, identifying his lover’s betrayal as the last straw: “If I can’t trust you, then damn it, Hannah / There’s no future, there’s no answer.”

The narrator’s relational woes are inseparable from a deeper spiritual malaise. On Modern Vampires, Koenig grapples with God for the first time, exploring the religious heritage handed down by his Jewish forebears. Critic Barry Lenser summarized this spiritual quest well in his review of the album:

Modern Vampires of the City is indeed a God-haunted work… Koenig doesn’t give any indication that he himself is a believer (more often just the opposite), but there is a recurring sense of engagement with God throughout the album, a sense of wrestling with the implications and possibilities of faith. By accident, or, more likely, by design, this builds and builds until Koenig puts everything on the table and addresses God directly.8

On “Unbelievers,” the narrator ponders the widespread religious conviction that those who reject Christian or Muslim dogmas are destined for eternal hellfire. Bewildered, he asks, “Is this the fate that half of the world has planned for me?” Existence already seems grim enough without the prospect of a torturous afterlife. Yet the narrator has become convinced that religion offers false comfort, and he defiantly refuses to take refuge in church:

We know the fire awaits unbelievers

All of the sinners the same

Girl, you and I will die unbelievers

Bound to the tracks of the train

Later, on “Everlasting Arms,” the narrator swings to the other side of the pendulum, referencing Deuteronomy 33:27 in his plea for God to shield him from death: “Hold me in your everlasting arms / Looked up, full of fear, trapped beneath a chandelier that’s going down.” He’s terrified of life without purpose or meaning, but he isn’t sure he wants to believe in a divine monarch who demands humanity’s allegiance:

If you’d been made to serve a master

You’d be frightened by the open hand, frightened by the hand

Could I be made to serve a master?

Well, I’m never gonna understand, never understand

Choral music crops up throughout Modern Vampires of the City, underscoring the album’s haunting tone and spiritual exploration. On “Worship You,” a chorus of voices delivers an anguished prayer:

We worshipped you, your red right hand

Won’t we see you once again?

In foreign soil, in foreign land

Who will guide us through the end?

Here, we discover that the narrator’s alienation isn’t a solitary struggle. His lyrics evoke the cries of the Jewish people, who were repeatedly driven from their homeland into exile, who still await the arrival of their messiah and the renewal of their holy city, and who still say, “Next year in Jerusalem!” at Passover, as Koenig himself does on “Finger Back.” Like the false promises of the modern world on “Obvious Bicycle,” religious expectations of deliverance from strife remain unfulfilled. And like his ancestors, Koenig struggles to get his bearings in unfamiliar territory, disillusioned by the silence of God.

The narrator’s anger reaches its thunderous crescendo on “Ya Hey.” Like Jacob, the Biblical patriarch who squared off with God in the desert and was renamed Israel, Koenig wrestles with the creator he doesn’t believe in. First, he asserts that the worship God receives doesn’t amount to anything: “Oh, good God / The faithless they don’t love you / The zealous hearts don’t love you.” Next, he castigates God for sitting idly by while his world goes to ruin: “And I can’t help but feel / That you’ve seen the mistake / But you let it go.” Finally, he accuses God of abandoning his people:

Through the fire and through the flames

You won’t even say your name

Only, “I am that I am”

But who could ever live that way?

In the Hebrew Bible, when asked for his name by the prophet Moses, the God of the Israelites replied, “I am that I am” (Exodus 3:14). This statement became the name “Yahweh,” a title so sacred that the Israelites refused to pronounce it aloud. On “Ya Hey,” a song whose chorus puns on the divine name, Koenig frames God’s response to Moses as an evasion – a choice to remain hidden rather than to deal directly with his people. The blaze of human suffering burns unchecked, as it has for thousands of years, and still God refuses to step in and right his world. As the flames of the narrator’s rant subside, guttering down to ashes, the choirs on “Hudson” sound a funeral dirge. The heavens remain silent. God (if he ever existed) hasn’t reversed the tide of suffering and death, and the narrator’s mortality still looms on the horizon. It seems the world he loved was against him from the start. As wrenching as it sounds, Koenig’s question in the second verse of “Ya Hey” seems the only fitting response: “Oh, the motherland don’t love you / The fatherland don’t love you / So why love anything?”

Conclusion

At last, the storms which have swept the landscape of Vampire Weekend’s third record fade, giving way to the soft piano and soothing harmonies on the album’s finisher, “Young Lion.” According to band member Rostam Batmanglij, the song’s lyric was inspired by a memorable encounter with a stranger that Ezra Koenig had at a Dunkin Donuts in Brooklyn. On his way to the studio to finish recording Contra, Koenig was stopped by an elderly Rastafarian man, who said these words to him: “You take your time, young lion.”9

The stranger’s comment is a fitting finale to a record steeped in existential crisis – perhaps the only conclusion that makes sense. At this point on the album, none of our questions have been answered, none of our fears relieved. Assurances that used to comfort us would feel glib after what we’ve just heard. If we’re as honest as Ezra Koenig, the world looks far bleaker than it did during our youth. All we’re left with, in the end, is a simple encouragement from those who’ve gone before us to keep going ourselves – to patiently live our questions, as the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke recommended,10 acknowledging the messiness and mystery of reality as we make peace with our own limitations. This will become the central theme of Vampire Weekend’s next album, Father of the Bride, a work that I’ll explore in-depth in a future post.

Ultimately, like the stranger who inspired “Young Lion,” the members of Vampire Weekend exhort us to hold on to our tickets, at least for a little bit longer. We might not know where we’re going. Even if we did, we might never make it there. Yet the wilderness has its own grandeur, and sorrows beautifully sung still bind us together with our fellow travelers, carrying us through the night.

Click below for the fourth chapter of my Vampire Weekend series!

References

1. Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, FSG, 1990.

2. Popova, Maria. Figuring. New York, Vintage Books, 2019.

3. Battan, Carrie. “Feature: Vampire Weekend.” Pitchfork, 7 May 2013.

4. Micallef, Ken. “Nothing As It Seems.” Electronic Musician, June 2014.

5. “Modern Vampires of the City.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_Vampires_of_the_City.

6. Rosen, Christopher. “Grammy Winners List 2014: Who Took Home Awards On Music’s Biggest Night?” The Huffington Post, 26 January 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/grammy-winners-list_n_4646243.

7. “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” Rolling Stone, 22 September 2020, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/best-albums-of-all-time-1062063/.

8. Lenser, Barry. “God and Man on ‘Modern Vampires of the City.'” PopMatters, 5 June 2013, https://www.popmatters.com/172143-god-and-man-on-modern-vampires-of-the-city-2495751338.html.

9. “Young Lion.” Genius, https://genius.com/Vampire-weekend-young-lion-lyrics.

10. Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters to a Young Poet. San Rafael, California, New World Library, 1992.