I still love the sea, despite the fact that it almost ruined my life.

On a windy day in the fall of 2017, while bodysurfing in the Indian Ocean, I was caught off guard by a huge wave that slammed my head against the seabed and swept the rest of my body over it. The experience remains vivid years later — I can still taste the saltwater that flooded my mouth, hear the sickening crunch in my neck, and feel my hands clawing at the sandy bottom of the inlet in a vain attempt to slow myself down. Seconds later, when the wave subsided, I lurched to my feet and stumbled toward shore. For two days, I couldn’t open my mouth without deep pain and pressure in the hinges of my jaw, which was even more worrying than it might sound. I’d been diagnosed with craniocervical instability — a rare disorder that afflicts the upper spine and base of the skull and had left more than one member of my family bedridden — just before my trip to Southeast Asia. The neurosurgeon who’d read my MRI results joked that I should be fine to travel, so long as I refrained from boxing. I don’t doubt that the watery one-two punch of breaker and undertow could’ve snapped my neck, and I’m grateful that didn’t happen. Yet, surprisingly, what has stayed with me over the years isn’t the anxiety caused by this injury; rather, it’s the memory of being caught in the clutches of the sea — that terrifying loss of control at the mercy of forces which didn’t know or care that I existed.

In retrospect, that big wave now seems like a microcosm of the wild half-year that surrounded it. I’d traveled to Southeast Asia as a senior in college, eager to participate in a six-month internship with an undercover missionary organization (Yep, it’s a long story). I’d never spent extended time away from my cultural and religious communities before, and instead of dipping my toes into this notoriously disorienting experience, I’d chucked off my snorkel and flippers and belly-flopped into the deep end.

My teammates overseas believed that God had called them to share Jesus’ love with the poorest of Asia’s poor. To accomplish this task, they’d moved their families into a slum, where they lived and labored with undocumented migrants who scavenged recyclable materials from city dumps and waste bins. You might not believe this, but the fact that the plywood shack where I slept was infested with large flying cockroaches wasn’t the toughest part of the trip. I was an outsider in a community where none of my neighbors spoke English, where everyone practiced Islam, and where my pale skin signaled levels of socioeconomic privilege that my neighbors couldn’t fathom. The experience of diving into their world was overwhelming, and it threw my young faith for a loop. My journals from those six months are filled with difficult questions: How do the evangelical teachings that I’ve inherited apply to people living in abject poverty? Are all of my neighbors destined for hellfire simply because they haven’t accepted Christ? Where is God in the midst of their suffering, and why do I have a return ticket home from circumstances which they may never escape? My bodysurfing injury, sustained during a weekend retreat from the daily grind of slum life, tossed another loaded query into the mix: Why would God intensify my suffering precisely when I’m trying my hardest to do his will?

These theological waters might’ve been deep, but they weren’t uncharted. Christianity had given me a framework for navigating upheaval and uncertainty — the intrinsic chaos of existence that, throughout the pages of the Bible, is represented using imagery of the sea. In Genesis 1, God creates the world by driving back a “formless and void” primordial ocean. In Exodus 14, he leads his chosen people to freedom by parting the Red Sea. This deliverance à la H2O becomes a motif; Biblical psalmists and prophets routinely extol Yahweh as one who restrains the sea and subdues its monsters — most notably Leviathan, a fire-breathing dragon that embodies all the power and unpredictability of the deep. Later, in the New Testament, Jesus displays his divinity by walking on water and calming a storm on the Sea of Galilee. And in the closing chapters of the Bible, God establishes his New Jerusalem after vanquishing the ocean itself: “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more” (Revelation 21:1).

The take-aways from these passages seemed clear: Life’s chaos was a temporary condition, nothing happened outside of God’s control, and Christians should respond to the unknown by taking refuge in the known — in the scriptures, the gathering of the saints, and communion with Christ. If I held fast to these truths, I was often told, then God would keep my faith afloat. Sure, the questions raised by my time overseas were troubling, but as I readjusted to familiar rhythms of life in the U.S., I became adept at absorbing their impact and riding them out. What I couldn’t see, waist-deep in my attempts to carry on as before, was that another wave of doubt was coming — one that would flip my entire world on its head.

Four years after my college graduation, I became petrified that I might lose my faith. Questions that I’d encountered in Southeast Asia had resurfaced, and my OCD brain had — for lack of a better word — gone apeshit, prompting a year-long quest to quell lingering doubts with obsessive research. Spoiler alert… it didn’t work. No matter how fiercely I bailed water with Christian apologetic arguments, facts about failed prophecy, the dubious historicity of the New Testament, and the problematic moral character of Yahweh kept washing over the sides of my boat. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I hadn’t been told the whole story — that the world was far bigger than my scriptures let on — and this wasn’t a welcome realization. Since childhood, I’d been taught that life outside the church was defined by chaos. Without God’s divine law to restrain my sin nature, how would I avoid sinking into moral depravity? How could I make decisions without the Holy Spirit’s guidance? If life ended at death, didn’t that obliterate any meaning that I might make during my lifetime? In other words, if I abandoned ship now, wasn’t I at the mercy of Leviathan?

Faced with a world that refuses to fit neatly within religious boundaries, religious people have three options: They can retreat from the world in a doomed attempt to shore up those boundaries, give up belief entirely, or attempt to make peace with realities that confound their paradigms. For a while, I took the third option, drawing comfort from the works of authors like Frederick Buechner. In his book Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale, Buechner explores the variegated tumult of life that churns beneath all our language and dogma. He begins with a New Testament passage in which a soon-to-be-crucified Christ responds to the Roman governor’s interrogations — “What is truth?” — with silence (Mark 15:1–5, John 18:38). From this cryptic passage, Buechner concludes that the Gospel — the “good news” of Christianity — is silence before it is spoken, since reality itself can’t be contained in words and is rather more akin to “the evening news, the television news, but with the sound turned off”:

Picture that then, the video without the audio, the news with, for the moment, no words to explain it or explain it away, no words to cushion or sharpen the shock of it, no definition given to dispose of it with such as a fire, a battle, a strike, a treaty, a beauty, an accident. Just the thing itself, life itself, or as much of it as the screen can hold, flickering away in the dark of the room. A man is making a speech outside on a flight of stone steps with one fist going up and down, his lips moving, a single wisp of hair lifted up by the breeze like a feather… A beautiful young woman in a long dress sits down as a piano, and a pair of blacks carrying a body on a stretcher between them hotfoot it down a city street in a running crouch while from high windows snipers’ bullets fly out silent as a dream. A great ship cuts through the water…

Buechner’s silent TV analogy perfectly evokes the mysterious quality of existence without explanation — the tidal wave of sights and sounds that crashes over each of us upon our gasping entry into the world. Words accumulate as we grow, enabling us to chart a course through life’s chaos, but that primordial splash of mystery never fully goes away. We may feel it when a symphony’s crescendo leaves us tongue-tied, when the mountains that we’ve read about in dozens of paperback novels stretch higher than we could have imagined, or when the words in our blog post about the shortfalls of language never seem quite right (I’m speaking generally, of course). Buechner drives the point home with a tongue-in-cheek story about (fittingly, in the context of this essay) head trauma:

The crazy Zen monk holds a stick in his hand and says, ‘What have I got in my hand?’ and the eager searcher after truth but only after a particular truth says, ‘It is a stick.’ Then the monk hits the man over the head with the stick as he richly deserves and says, ‘No, that’s what it is,’ or doesn’t even bother to say it.

Buechner goes on to distinguish between the “particular truth” expressed in words and “the truth” itself — life without human interpretation. Biblical prophets, he says, wrote many particular truths about their time and place. Rarely, however, did these authors touch the bedrock of truth itself. When they did, it was only through the elusive, elliptical cadences of poetry. The upshot of Buechner’s argument seems to be that, beyond their surface references to concrete historical events, the stories of the Bible are primarily valuable as myth and metaphor — as imperfect, sometimes accurate, and occasionally profound maps of ever-shifting seas. Yet Buechner maintains that the Biblical narrative adds up to — and ultimately contains — the essence of reality. After laying out scriptural tenets of humanity’s sinfulness, its need for redemption, and its dependence on Jesus’ atonement, he says of these claims: “All together they are the truth.”

Buechner’s writing is undeniably beautiful. Unlike many religious people, he leaves great space within his worldview for complexity, incongruity, and reformulation. But there’s a problem here, and it’s pretty glaring. You can’t say that reality — Truth with a capital T — exists beyond the bounds of language while also contending that your religion’s holy book encapsulates reality. That’s like saying that the rough-edged pieces of your Christmas jigsaw puzzle are equivalent to real kittens in stockings once they’re fully assembled. Buechner’s distinction between “the truth” and “particular truths” also gets fuzzy when applied to Christian scripture; we might well ask why core Biblical doctrines — humanity’s fall into original sin, redemption through belief in Jesus’ blood sacrifice, imminent apocalyptic judgement, the rewards of heaven and the punishments of hell — aren’t just as particular, just as time-bound, and just as prone to error as their ancient authors’ ethical codes and accounts of historical events. If the Bible, with its narrow scope and numerous flaws, can encompass life’s universal ocean, then why can’t Muslim, Hindu, or Buddhist texts — or, for that matter, Tolstoy’s novels and Shakespeare’s plays?

Ultimately, Buechner’s acknowledgement of language’s limits rang truer than his attempts to brace traditional Christianity for life’s chaotic seas. In the fall of 2022, I finally surrendered to my doubts and came out to family and friends as a nonbeliever. Words can’t express how terrifying this transition was. Trying to describe it a therapist over Zoom, I imagined myself treading water in a fathomless sea. My legs needed to start kicking, but with no divine lights on the horizon, how could I be sure that I’d choose the right direction — or that I’d survive the journey at all? My categories for making sense of the world were gone, nothing around me looked familiar anymore, and it was hard to escape the conclusion that this trials would define the rest of my life, until it finally dragged me under.

Oddly enough, what brought comfort in this profoundly disorienting time was a documentary about fish guts.

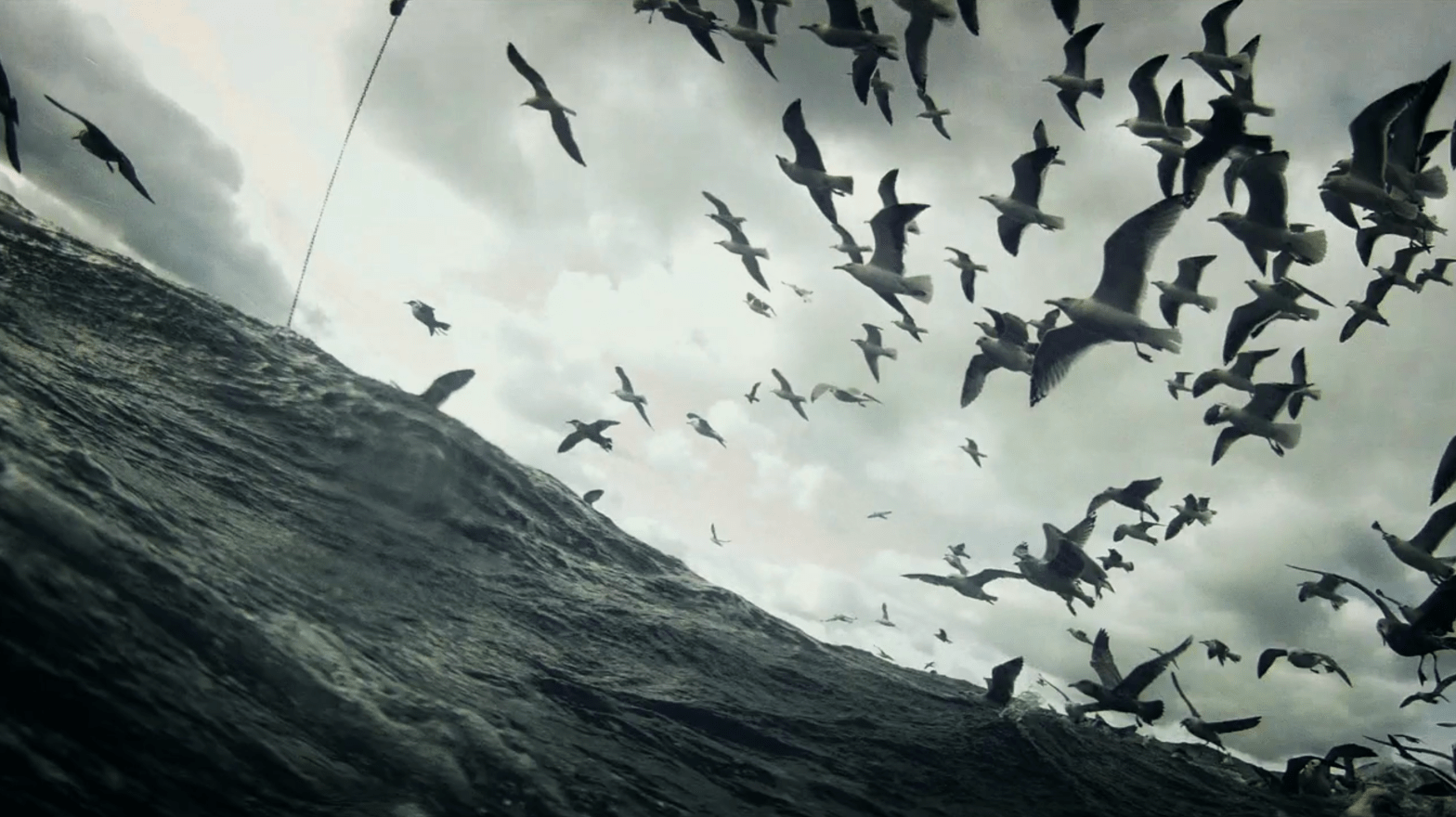

The 2012 film Leviathan, directed by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, opens with a quote from the book of Job that describes — you guessed it — the Bible’s legendary sea monster: “He maketh the deep boil like a pot… Upon earth there is not his like, who is made without fear.” It’s a fitting start. Not only is the documentary set in the same North Atlantic waters that inspired Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, but it’s also a depiction of chaos unlike any film in recent memory. The movie’s directors hail from the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard University, and they use GoPro cameras to immerse viewers in the sensory experience of life aboard a commercial fishing boat… with zero narration, story structure, or dialogue to make sense of that experience.

Fishermen pulling chains in the pre-dawn darkness. Severed heads of cod sloshing across the surface of the deck. A maelstrom of innumerable starfish. As each wordless sequence gives way to the next, you might find yourself recalling Buechner’s vision of life “with the sound turned off.” Except the sound isn’t turned off here; rather, it’s turned up to eleven, with the mechanical din of the ship’s passage adding percussion to the susurrous melodies of spray and tide. In what is perhaps their boldest artistic move, the filmmakers lash their cameras to poles which are alternately plunged underwater or thrust into the sky, forcing us to witness the ship from the perspective of the fish caught in its nets and the birds hovering above its wake. Now, if you’ve never wanted to know what it feels like to be chased, captured, and disemboweled by fishermen, this film might not be your cup of tea. However, if you allow yourself to sync up with Leviathan’s ebb and flow, two mysterious things begin to happen.

First, the beauty and brutality of life at sea become visceral realities instead of abstract concepts. It’s one thing to read statistics about the environmental toll of the fishing industry, another to see vast quantities of fish spilling through machinery like grain in a combine. Likewise, while the testimony of a fisherman might alert us to the human costs of capitalism, we learn something else entirely by spending extended time with sailors drenched by waves, ankle-deep in clam shells, and exhausted from repetitive movements. Rarely has Tennyson’s “nature red in tooth and claw” — the apparent absurdity and indifference of the cosmos — been more starkly displayed. Yet these grim details also throw the film’s moments of transcendence into sharper relief. Night bleeds into the flush of sunrise. Flecks of water catch sunlight and sparkle like diamonds. And, in one of the most awe-inspiring scenes ever put to film, a lofty camera flips upside-down in a flock of hundreds of seagulls, winging their way above the tempest like Biblical spirits at the dawn of creation (Genesis 1:2).

Leviathan reminds me that uncertainty is a double-edged sword — frightening and liberating in equal measure. The decision to sit with our questions and to resist dogmatic solutions to them can be very uncomfortable, but it also opens us up to new discoveries, sensitizing us to the miracle and mystery of existence in ways that can transform us.

Before traveling to Southeast Asia, I’d studied poverty in depth. Yet the experience of digging through trash bags and shouldering sacks of recyclable materials with slum-dwellers enabled me to understand it in ways that words couldn’t — in my skin and joints and muscles. Similarly, I’d heard countless sermons on the eternal fate of unbelievers, and I’d listened as Christian apologists trumpeted the superiority of the gospel over Muslim doctrine. Yet the experience of getting to know actual Muslims — through conversations over coffee, meals shared in plywood shacks, visits to mosques, and theological discussions (You better believe I tried and failed to expound the Trinity to my neighbors) — made Jesus’ fiery pronouncements of doom and damnation feel incredibly prosaic. When I stopped picturing my neighbors as souls to be saved, their physical suffering weighed heavier on my conscience; I yearned to play some small role in fixing the systems that held them down. Conversely, their joy, resilience, hospitality, and creativity soared higher in my estimation, like the handcrafted kites their children flew above the trash heaps.

I’ll never forget standing by the polluted stream that bisected the slum, listening to the adhan (call to prayer) as night fell, and realizing — perhaps for the first time — how little I really knew, how small I was in the grand scheme of things, and how grateful I felt to be a part of it all. Years later, when I finally set the Bible aside, questions about the origin of the universe, the enigma of consciousness, the scope of Darwinian evolution, and the brute fact of existence kindled awe that the words “And God said” couldn’t replicate. The conviction that life on Earth was a prelude to a glorious future gave way to a desire to savor life’s fleeting wonders.

The film Leviathan also highlights the empathy that emerges from mutual disorientation. As I watch it, I find myself asking: Who am I supposed to root for here? The fish plucked from the sea? The birds hurrying to keep up with the ship? The crew members fighting to provide for themselves and their families? With no narrator to direct our sympathies, and with camera shots that mimic the eyes of fish and fishermen alike (Trust me, there are lots of fish eyes in this movie…), our labels and categories become irrelevant. Instead of searching for “good guys” and “bad guys,” we begin to see cod, seagulls, sailors, and ship as a single organism, bound together by their shared struggle to navigate the depths.

When I renounced faith in Jesus Christ, part of me expected to drown in the chaos of life without God. I’d be lying if I said that fear has ever fully dissipated. At times, I yearn for the stability that church and scripture provided with an ache that can’t be articulated in words. Nevertheless, I feel a newfound kinship with the planet, with my cousins and distant relatives in the animal kingdom, and with the diverse humans I meet each day. When I’m tempted to lament my mortality or to wallow in my confusion, I take heart from the millions of atheists, agnostics, and freethinkers who turn bewilderment into curiosity each day; who grow compassion for the “other” from seeds of personal hardship; and who — with the gift of a Nietzschean rose — thank the abyss for awakening them to life’s wordless glory. Suffering, as the playwright Thornton Wilder once wrote, becomes the key to empathy:

Without your wounds where would your power be? It is your melancholy that makes your low voice tremble into the hearts of men and women. The very angels themselves cannot persuade the wretched and blundering children on earth as can one human being broken on the wheels of living. In Love’s service, only wounded soldiers can serve. Physician, draw back.

Not for nothing is Leviathan feared. For all its grandeur, the sea is a harsh and lonesome place. Yet, after three years of treading its waters, I can honestly say that I wouldn’t trade the wonders my eyes have seen or the relationships I’ve gained for the comforts of life on deck. As scary as that big wave in Southeast Asia was, there was something thrilling about taking its full force and living to tell the tale. No written words will ever capture it.

“Sell your cleverness,” advises the Sufi poet Rumi, “and buy bewilderment. Cleverness is mere opinion, bewilderment is intuition.” While I’ve left religion behind, I still admire the monks and mystics who, like Frederick Buechner, suggest that God is found in silence. Why settle for cheap explanations when we can feel — in our bones as well as our souls — the tactile intimacy and limitless expanse of the cosmos we call home?

In the year before I became an atheist, the pastor at my evangelical church preached a sermon on Revelation 21. “As difficult as this might be to imagine,” he said, “there will be no ocean in heaven.” Though I agreed with his exegesis, I found myself bristling at the notion that God might one day obliterate the sea forever. Even then, I sensed a truth that would take years to unpack — the reality that chaos is our ancestral homeland, as the book of Genesis inadvertently suggests, not a foe to be conquered. Yes, it almost ruined my life, but I love it anyway. Herman Melville, that salty old mariner who knew all too well the crush and grace of the sea, expressed my feelings perfectly when he penned the following words in Moby Dick:

All deep, earnest thinking is but the intrepid effort of the soul to keep the open independence of her sea… As in landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God — so better is it to perish in that howling infinite, than be ingloriously dashed upon the lee.

Or, as Ella Mine puts it in the opening of song of her album Dream War:

Though there are shadows dancing

Just beneath the waves

I wanna jump in anyway