Many people, on encountering scenes of beauty, whip out their phones and begin snapping photos. I take mental pictures. Whether I’m gazing up at the watercolor wash of a sunset, watching rainwater pool beside streets and sidewalks, or stopping to appreciate the blossoms on a magnolia tree, I spend lots of time looking at things that catch my eye. You’ve probably run into me at zoos or museums; I’m that guy who stands in front of Rembrandt paintings and chimpanzee enclosures (and in front of you) for a few minutes too long.

These pauses aren’t just about aesthetics. I’m chasing a feeling — one that you’ve probably experienced yourself. See if this sounds familiar: You’re staring at an everyday vista — beautiful but not particularly unique — and suddenly it’s like an invisible curtain is drawn back. Your surroundings shine with a vibrancy that takes your breath away, the moment feels afire with meaning, and then the vision vanishes as quickly as it appeared. The return to normalcy leaves you blinking and bewildered. What power transfigured this seemingly ordinary view? Where did all that wonder come from, where did it go, and can it be recaptured? As you turn away from the sight, longing for what was lost fills your chest cavity with a palpable ache.

The Christian author and literary critic Clive Staples (C.S.) Lewis had a word for this feeling: sehnsucht. In his autobiography Surprised by Joy, Lewis defines this German term as “a single, unendurable sense of desire and loss.” He shares a childhood experience of sehnsucht prompted by the sight of a flowering currant bush near his home in Belfast, Ireland:

It is difficult to find words strong enough for the sensation which came over me; Milton’s ‘enormous bliss’ of Eden (giving the full, ancient meaning to enormous) comes somewhere near to it. It was a sensation, of course, of desire; but desire for what?… Before I knew what I desired, the desire itself was gone, the whole glimpse… withdrawn, the world turned commonplace again, or only stirred by a longing for the longing that had just ceased.

According to Lewis, sehnsucht is fleeting yet accompanied by a sense of “incalculable importance.” It’s also pleasurable and painful in equal measure; later in his autobiography, Lewis refers to it as “the stab of joy” that is “almost like heartbreak.” These strange contradictions, he argues, reveal the emotion’s divine origin. Sehnsucht is a preview of the paradise that awaits followers of Jesus Christ. In his book Mere Christianity, the author distills this thought into a syllogism: “If I find in myself desires which nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world.”

If, like me, you were raised in American evangelicalism, you’ve likely heard this quote. The Baptist churches that I attended gave Catholic veneration of saints a side-eye, but our reverence for C.S. Lewis wasn’t too different. The Cambridge don loomed large in my young imagination, so much so that I attended Wheaton College in Illinois because they owned his desk (I’m only slightly exaggerating). His writings on sehnsucht have inspired countless sermons, stories, and songs, and they’re a popular apologetic for Christian faith. If the beauty of this world doesn’t quench our spiritual thirst, believers contend, then this proves that we’re meant for more — a relationship with the creator of beauty that lasts beyond the grave.

My acceptance of this argument shaped my faith in profound ways, and it also complicated my decision to leave the Christian church in November of 2022. When people ask about my experience of deconversion, I tell them that it felt like someone had taken a giant vacuum cleaner and sucked all the magic out of the world. Events that once inspired worship now raised painful questions: Was the awe that accompanied these “religious experiences” a sign of transcendence, or was it an accident of brain chemistry? Could any meaning be found in wonders that had emerged through a slow, mechanistic process of evolution? And if the beauty that stirred my longings wasn’t a love letter penned by a divine hand, how could I escape the conclusion that it was lifeless and arbitrary?

In his book A Secular Age, philosopher Charles Taylor makes a claim that echoes Lewis’ notion of sehnsucht: “All joy strives for eternity, because it loses some of its sense if it doesn’t last.” Senseless is exactly how post-Christian life seemed. For decades, I had awaited a cosmic redemption — “a new heaven and a new earth” (Revelation 21:1) that would answer my deepest desires. Now, staring down the barrel of my mortality, I realized that my yearning would never be fulfilled. As singer-songwriter Ben Shive wrote, there was “nothing for the ache.”

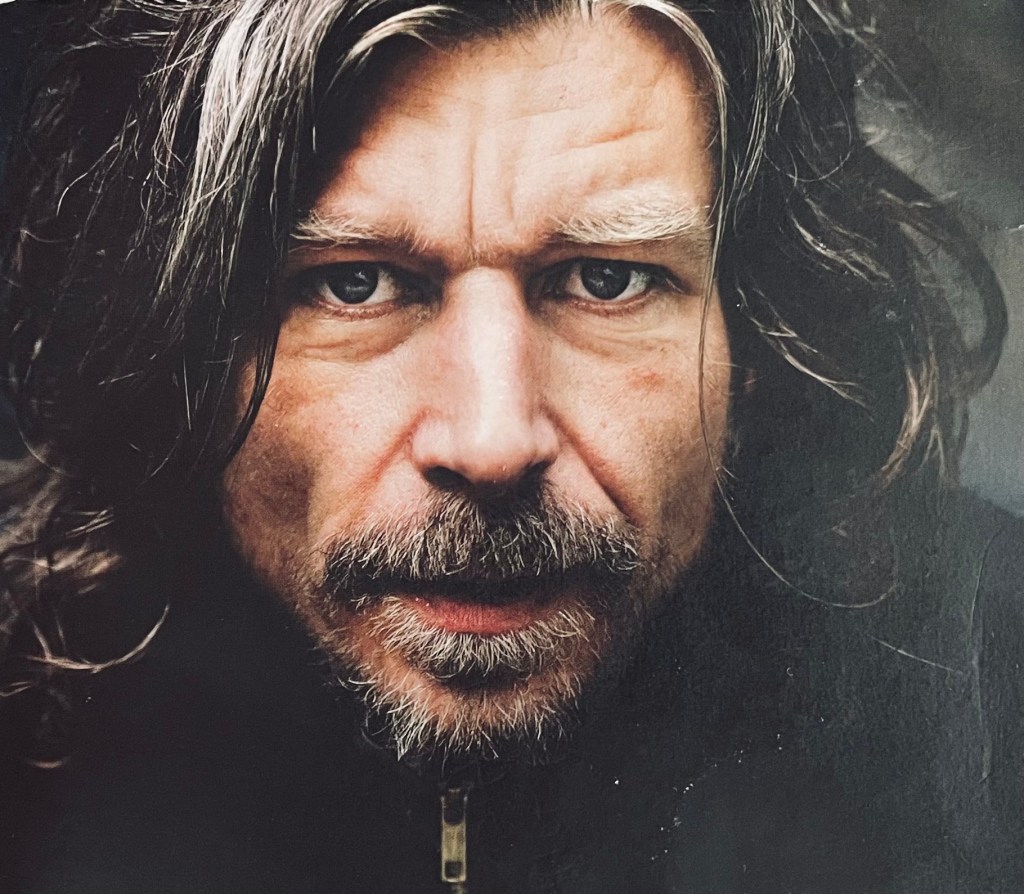

But was Lewis correct? Is eternity the “only logical explanation” for our feelings of wonderment? Are those who abandon religion doomed to wander through a disenchanted world? These questions nagged at me, and then (as often happens) I found solace in literature — specifically, a six-volume, 3,600-page autobiographical novel series by Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard.

These books, collectively titled My Struggle, describe the author’s daily life in exhaustive detail; visits to the grocery store, conversations with children, funeral arrangements, house parties with friends, and trips to nearby cities can stretch for twenty pages or more. “Why would you do that to yourself?” you may be asking, and it’s a fair question. I can only say that Knausgaard’s prose makes each moment shine, no matter how mundane it may seem. Furthermore, as I’ve pondered My Struggle, I’ve realized that the book answers the challenge posed by Surprised by Joy and Mere Christianity, exposing the fatal flaw in C.S. Lewis’ most famous idea.

In the first volume of My Struggle, Knausgaard describes “those sudden states of clearsightedness that everyone must know, where for a few seconds you catch sight of another world from the one you were in a moment earlier, where the world seems to step forward and show itself for a brief glimpse before reverting and leaving everything as before.” He then relates one of these experiences, in which he is ambushed by feelings of awe while gazing at a sunset through the window of a commuter train:

I wasn’t thinking about anything in particular, just staring at the burning red ball in the sky and the pleasure that suffused me was so sharp and came with such intensity that it was indistinguishable from pain. What I experienced seemed to me to be of enormous significance. Enormous significance. When the moment had passed the feeling of significance did not diminish, but all of a sudden it became hard to place: exactly what was significant? And why? A train, an industrial area, sun, mist?

The parallels here to Lewis’ childhood epiphany are striking. In each experience, the setting is thoroughly mundane, yet it kindles astonishment in the observer; feelings of joy and heartache swirl together; the moment feels incredibly important (Knausgaard even uses the same word as Lewis — “enormous” — to describe it); and the end of the experience generates questions. If Knausgaard was a religious person, he might follow Lewis and frame this scene as a glimpse of divinity (Lewis’ run-in with a currant bush recalls the burning bush seen by Moses in Exodus 3; apparently, God likes using greenery for conference calls). However, the Norwegian interprets his own epiphany in profoundly different terms.

According to Lewis, experiences of sehnsucht are so remarkable that they make the rest of the world seem “commonplace” and “insignificant by comparison.” This contrast leads him to infer that something is fundamentally wrong with the world. Beauty fades, time passes too quickly, and life doesn’t satisfy as it should. Shouldn’t the situation be otherwise? Don’t these unpleasant facts prove that our current material world isn’t enough — that we were designed for elsewhere?

This argument fits snugly within a religious worldview. Over and over again, the Bible depicts our planet as foreign and inhospitable territory; Christians are “sojourners and exiles” (1 Peter 2:11) who are “not of the world” (John 15:19) and are “looking for the city that is to come” (Hebrews 13:14). The founders of the Christian church urged their followers to detach themselves from earthly concerns. “Set your minds on things that are above,” the apostle Paul wrote, “not on things that are on earth” (Colossians 3:2). The author of 1 John put it more bluntly — “Do not love the world of the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him” (1 John 2:15) — as did the author of James: “You adulterous people! Do you not know that friendship with the world is enmity with God?” (James 4:4). Christians may involve themselves in worldly careers and activities, but their real concern is the world to come, not this broken planet that is ultimately doomed to pass away (Revelation 21:5).

Growing up in the evangelical church, I often heard my life described in terms that rendered it insubstantial — it was a mist, a vapor, an echo, a shadow, a prelude, a foretaste of thrills to come. “Enjoy it,” people told me, “but don’t get attached. Your real home is right around the corner, and it’ll blow this puny cosmos out of the water.” Thus, while Lewis’ notion of sehnsucht might seem original, it merely recycles this age-old doctrine of the world’s inadequacy. The inevitable consequence of this doctrine is detachment — believers are admonished to focus their time and attention on what is eternal and to avoid caring too deeply for things that pass away.

Knausgaard understands this impulse. In book six of My Struggle, he writes:

I know what it means to see something without attaching yourself to it. Everything is there, houses, trees, cars, people, sky, earth, but something is missing nonetheless. You have not attached yourself to what you see, you do not belong to the world and can, if push comes to shove, just as well leave it.

However, attachment is the very thing Knausgaard is after. In his book This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom, Swedish philosopher Martin Hägglund highlights a phrase that recurs throughout the pages of My Struggle — Det gjelder å feste blikket — which he translates as follows: “Focus your gaze by attaching yourself to what you see.” This is what Knausgaard is doing by writing 3,600 pages on his everyday life. He isn’t a narcissist (or, as those who hate writing may imagine, a masochist). He’s paying attention to his surroundings, reflecting on his place within them, and savoring their beauty for its own sake. Moments of sehnsucht aren’t drawing him out of his world; they’re pushing him deeper into it.

This movement is also evident in his experience on the train. Knausgaard may sound like Lewis when he refers to “another world,” but his meaning becomes clear in the following sentence, where he says that “the world seems to step forward and show itself for a brief glimpse.” The wondrous place that Lewis sees when he encounters beauty isn’t, as he imagines, a distant or heavenly hereafter. It’s the world right in front of his nose, momentarily revealing itself — to eyes that have forgotten how to see — as the miracle it already is. Together, Knausgaard’s attempt to “focus the gaze” and his description of the world showing itself recall the finale of Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town, in which a ghost revisits a scene from her childhood and breaks down in tears, saying: “I can’t look at everything hard enough… Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you!”

If life’s majesty falls short of Lewis’ ideals, it’s only because he has grown accustomed to it. Gazing back from the vantage point of middle age, he views his childhood awe as evidence that the world’s beauty doesn’t satisfy. But I’d be willing to bet that his younger self didn’t feel that way (let me know if I’m wrong, Clive). Children aren’t obsessed with eternal fulfillment or discouraged by the dissipation of their excitement. Each transient discovery, whether it’s the sight of a first snowfall or the revelation that farts are inherently funny, propels them onward to the next — “further up and further in,” as Lewis himself writes in The Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis uses this phrase to describe a Christian’s ascent into the glories of paradise (“Aslan’s country”), but it’s just as applicable to a planet whose manifold wonders — autumn leaves, soccer games, blue whales, rock songs, bedtime stories, first kisses, star-filled skies, belly laughs, mountain ranges, and late-night conversations — have always been more than enough.

Like Knausgaard, we may want to savor life’s temporary pleasures. Yet is Charles Taylor right when he says that joy “loses some of its sense if it doesn’t last”? If nothing satisfies us fully, and if our desires end at death, doesn’t that make our pursuit of beauty meaningless? Depends how you look at it. In the second volume of My Struggle, Knausgaard writes that “meaning is not something we are given, but which we give. Death makes life meaningless because everything we have ever striven for ceases when life does, and it makes life meaningful, too, because its presence makes the little we have of it indispensable, every moment precious.” In other words, the value of our surroundings isn’t dependent on their endless existence or bestowed by God’s decree. It emerges from our decision to notice and appreciate the beauty they hold — a choice that remains open to us for as long as we live. Indeed, as Knausgaard suggests, the finitude of that beauty is integral to our perception of its meaningfulness. This explains the ache that accompanies our experiences of sehnsucht. Hägglund elaborates in his analysis of Knausgaard’s work:

The experience of beauty is…a stab in the heart, and [Knausgaard] is seized by the desire to hold on to everything that will not last… When he is seized by the colors of the world, the sense that they will fade is part of what makes them absorbing, part of what compels him to pay attention to their qualities and linger over their beauty… Only someone who is torn open by time can be moved and affected. Only someone who is finite can sense the miracle of being alive.

I still spend long periods of time staring at flowers and rainfall and sunsets. During some of these pauses — infrequently but often enough to keep me coming back — that old familiar ache fills my chest. This sehnsucht-longing used to bring C.S. Lewis to mind, but now it makes me think of Karl Ove Knausgaard. The Norwegian author is right: True joy isn’t a destination that we reach, and it doesn’t lie beyond the grave. Rather, it’s what we choose to make of this brief yet beautiful journey that we find ourselves on. Considered in this light, Lewis’ decision to pine for another world becomes a grave error. Philosopher Albert Camus says it best: “If there is a sin against this life, it consists, perhaps, not so much in despairing of life as in hoping for another life and eluding the quiet grandeur of this one.”